I’ll never forget my first morning in Italy. Bleary-eyed from travel but buzzing with anticipation, I arrived at the Vatican Museums just as the doors opened. What followed was an overwhelming flood of masterpieces—ancient sculptures, Renaissance tapestries, corridors lined with gold. But nothing prepared me for the moment I stepped inside the Sistine Chapel.

Craning my neck to take in Michelangelo’s ceiling, I felt my understanding of art shift forever. Those vibrant frescoes weren’t just paintings; they were a portal to divine genius. The way Adam’s finger nearly touched God’s, the terror and hope in The Last Judgment—I left with my head spinning, convinced I’d seen enough art to last a lifetime.

Then I went to Florence.

The Uffizi Gallery, set in the very heart of the Renaissance, proved me wonderfully wrong. Room after room revealed Botticelli’s ethereal goddesses, Caravaggio’s dramatic lighting, and Raphael’s perfect harmonies. It was there I realized Italian art isn’t confined to museums—it spills into churches, piazzas, and cobblestone streets.

Over many return trips, I’ve chased that same thrill of discovery. And while Italy offers endless artistic treasures, some masterpieces stand above the rest. In this post, I’ll share 15 paintings that stopped me in my tracks—works that redefine beauty, skill, and emotional power.

Now I’d love to hear from you: Which pieces would make your list? Did I miss a hidden gem or overrate a famous name? Let’s debate in the comments—after all, half the joy of Italian art is sharing the wonder it inspires.

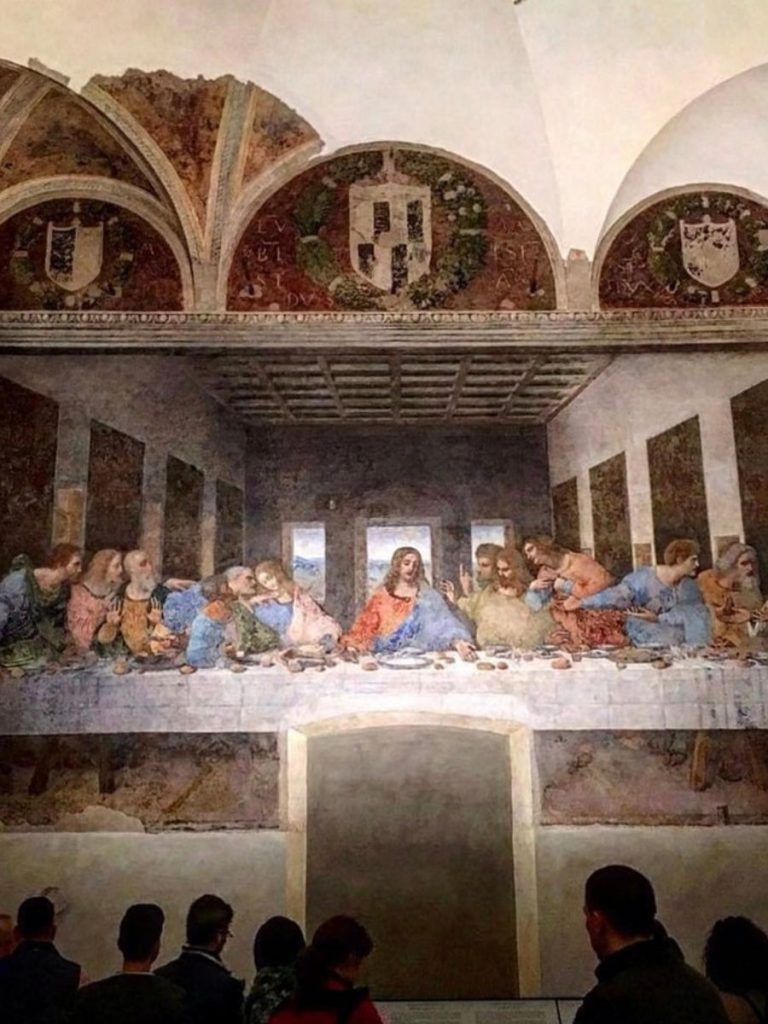

1. Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1498) – Milan

Hidden away in the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Leonardo’s The Last Supper remains one of the most revolutionary—and fragile—works in art history. Unlike traditional frescoes, Leonardo experimented with an oil-tempera hybrid technique that began deteriorating almost immediately after completion. What survives today is actually multiple layers of restoration work, with only fragments of Leonardo’s original brushstrokes remaining.

The painting’s genius lies in its psychological complexity. Leonardo captures the precise moment when Jesus announces his impending betrayal, with each apostle reacting distinctly—from Peter’s angry grip on a knife to Judas’s shadowy withdrawal. The composition’s vanishing point aligns perfectly with Christ’s right temple, drawing all attention to his calm, resigned expression at the center of the storm. The empty space above Jesus’ head creates an unsettling void, while the three windows behind him may symbolize the Holy Trinity.

Travel Tip: Due to strict conservation measures, visitors get just 15 minutes with the painting. Book tickets at least 2-3 months in advance, and arrive early to study the excellent exhibits on its restoration history in the adjacent museum.

2. Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (1485) – Florence

In Room 10-14 of Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus floats in ethereal perfection. Commissioned by the Medici family, this work represents the Renaissance’s rediscovery of classical mythology—Venus, goddess of love, born from sea foam and carried to shore on a giant scallop shell. The painting nearly vanished during Savonarola’s 1497 “Bonfire of the Vanities,” when Florentines were convinced to burn “sinful” artworks.

Botticelli’s style is unmistakable: the elongated figures, flowing drapery, and delicate coloring create a dreamlike quality. Venus stands in modest contrapposto, her golden tresses strategically covering her nakedness. To her left, Zephyr and Aura blow her gently toward land; to her right, a Hora (seasonal nymph) prepares to clothe her in a flowered mantle. The painting’s background, with its simplified sea and shoreline, focuses all attention on the figures, while the gold accents would have shimmered in candlelight when first displayed.

Travel Tip: Head straight to Botticelli’s room at opening time (8:15 AM) to enjoy this masterpiece in relative peace before crowds arrive around 10 AM.

3. Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam (1512) – Vatican City

Among the Sistine Chapel’s dazzling ceiling frescoes, The Creation of Adam stands as perhaps the most iconic image in Western art. Michelangelo’s genius lies in what he doesn’t paint—that electrifying gap between God’s outstretched finger and Adam’s languid hand, containing all the potential of humanity. Recent scholarship suggests the red cloak surrounding God resembles a cross-section of the human brain, possibly symbolizing the divine gift of intellect.

The composition is deceptively simple. Adam, reclining on a barren slope, mirrors God’s posture but lacks his vitality. The figure of Eve, not yet created, gazes out from under God’s arm, while various angels—including one who might represent the unborn Virgin Mary—complete the celestial entourage. Michelangelo painted this lying on his back for four grueling years, and the physical strain shows in the exaggerated musculature of his figures—a signature style that would influence artists for centuries.

Travel Tip: Book a small-group early morning Vatican tour (around 7:30 AM entry) to experience the Sistine Chapel in contemplative silence before the crowds descend.

4. Raphael’s The School of Athens (1511) – Vatican City

In the Stanza della Segnatura—Pope Julius II’s private library—Raphael created what might be the ultimate tribute to human reason. The School of Athens gathers history’s greatest philosophers under the soaring arches of an imaginary Roman basilica that recalls Bramante’s designs for New St. Peter’s. At the composition’s heart, Plato (modeled after Leonardo da Vinci) points upward to the realm of ideals while Aristotle (perhaps Raphael’s contemporary Bramante) gestures toward the earth, embodying their philosophical divide.

Raphael populated this intellectual summit with portraits of his contemporaries: Michelangelo as the brooding Heraclitus in the foreground, Euclid (as architect Bramante) demonstrating geometry, and even himself as the young painter peeking from the far right corner. The perspective draws the eye deep into the painting, making viewers feel they could step into this temple of wisdom. The color palette—dominated by earthy ochres and cool blues—creates perfect balance, while the architectural setting reflects Renaissance ideals of harmony and proportion.

Travel Tip: Visit in late afternoon (after 3 PM) when most tour groups have moved on. Bring binoculars to appreciate the incredible details in the upper sections.

5. Caravaggio’s The Calling of St. Matthew (1600) – Rome

In the quiet Contarelli Chapel of San Luigi dei Francesi near Piazza Navona, Caravaggio’s revolutionary masterpiece stops visitors in their tracks. The painting shows the tax collector Matthew at his counting table when Christ unexpectedly appears to call him to discipleship. A shaft of divine light cuts through the tavern’s gloom, illuminating Matthew’s astonished face as he points to himself—”Who, me?”—while his colleagues remain engrossed in counting money.

Caravaggio’s signature chiaroscuro (dramatic light and shadow) makes the biblical story feel startlingly immediate. The figures wear 17th-century clothing, and the setting resembles a Roman dive bar more than a holy scene. Notice how Christ’s hand deliberately echoes Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam—but here, the divine touch is obscured by shadow, suggesting God’s mysterious ways. This was sacred art for the real world, and its gritty realism scandalized some while thrilling others.

Travel Tip: Bring €1 coins to illuminate the painting (the lighting is timed). Visit mid-morning (around 10 AM) on weekdays for quiet contemplation, and don’t miss Caravaggio’s other two paintings in the same chapel.

6. Titian’s Assumption of the Virgin (1518) – Venice

In Venice’s Frari Basilica, Titian’s monumental altarpiece still stuns visitors five centuries after its creation. The painting shows the Virgin Mary ascending to heaven in a swirl of golden light, her crimson robe billowing dramatically as astonished apostles reach upward. At the top, God the Father leans forward in anticipation, creating a dynamic diagonal composition that draws the eye from earth to heaven.

This work marked a turning point in Venetian art. Titian broke from tradition by showing the Assumption as a moment of explosive movement rather than static contemplation. The vibrant colors—especially the striking contrast between Mary’s blue mantle and the golden background—would have glowed in the candlelit church. When first unveiled, some clergy objected to its unconventional style, but the public adored it, establishing Titian as Venice’s leading painter.

Travel Tip: Visit in late morning when sunlight streams through the basilica’s windows, illuminating the painting’s colors. The nearby Pesaro Altarpiece (also by Titian) makes an excellent companion piece.

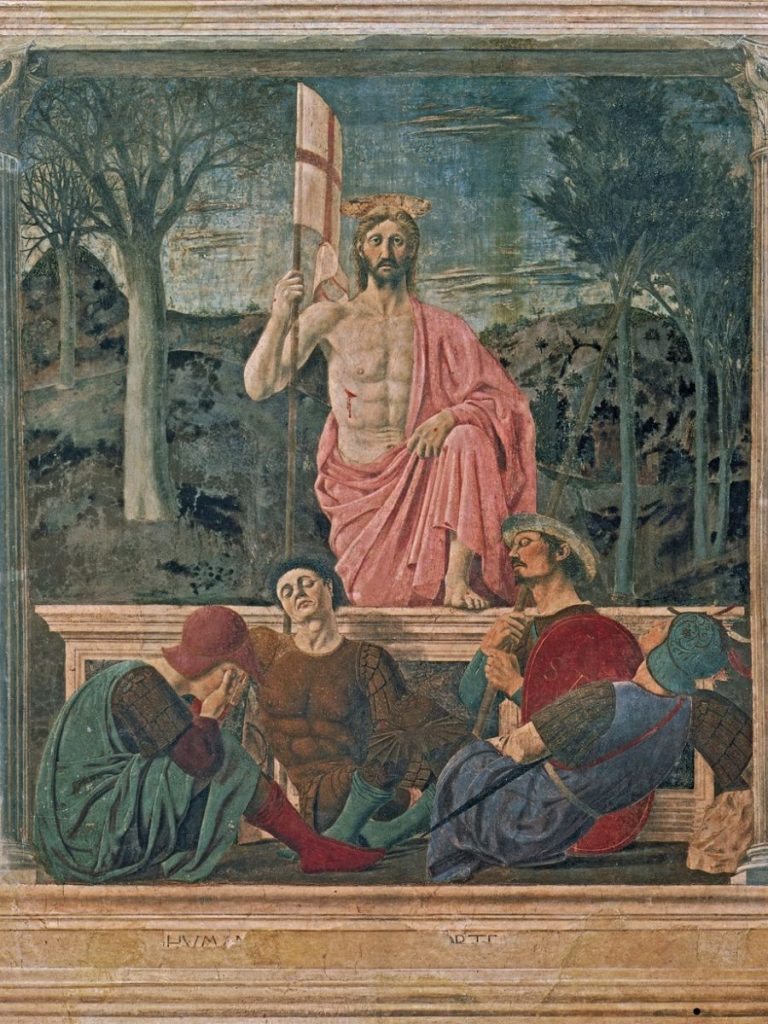

7. Piero della Francesca’s The Resurrection (1460s) – Sansepolcro

In the Museo Civico of this small Tuscan town, Piero’s haunting fresco shows Christ emerging from his tomb with an expression of quiet intensity. The composition divides neatly into two zones—the cold, geometric stillness of the soldiers below and the warm, living figure of Christ above. One sleeping soldier is said to be a self-portrait of Piero, his slack jaw contrasting with Christ’s alert gaze.

Piero’s mathematical precision is evident everywhere—from the perfect perspective of the tomb to the careful proportions of Christ’s figure. The dawn light, symbolizing both the resurrection and the town’s namesake (“Holy Sepulchre”), bathes the scene in an otherworldly glow. This painting was nearly destroyed during WWII when a British artillery officer, recalling Aldous Huxley’s description of it as “the greatest painting in the world,” countermanded orders to shell the town.

Travel Tip: Sansepolcro makes an excellent day trip from Arezzo or Florence. Time your visit for the midday light when the museum’s illumination best showcases the fresco’s colors.

8. Botticelli’s Primavera (1482) – Florence

Back in the Uffizi’s Botticelli rooms, Primavera is a visual symphony of springtime symbolism. Set in a citrus grove (a Medici family symbol), the painting features over 500 identifiable plant species surrounding mythological figures. At center, Venus stands in a Gothic arch formed by the trees, with Cupid hovering above. To her right, the Three Graces dance while Mercury chases away winter clouds. To her left, Flora scatters flowers as Zephyr chases the nymph Chloris.

The painting’s meaning remains debated—is it a Neoplatonic allegory of spiritual love? A celebration of Medici weddings? A seasonal calendar? What’s undeniable is its mesmerizing beauty. Botticelli’s flowing lines create rhythmic movement across the canvas, while the delicate colors (especially the flowers’ pinks and whites) showcase his mastery of tempera technique. The figures’ elongated proportions and dreamy expressions give the scene an ethereal quality that feels both timeless and deeply personal.

Travel Tip: View Primavera and Birth of Venus back-to-back to appreciate how Botticelli’s style evolved. The Uffizi’s recent reordering places them in adjacent rooms.

9. Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment (1541) – Vatican City

The Sistine Chapel’s terrifying west wall shows Christ’s apocalyptic return, painted by Michelangelo 25 years after completing the ceiling. Unlike traditional symmetrical compositions, Michelangelo creates a swirling vortex of figures—the saved rising joyfully at left, the damned plunging in terror at right. At center, a beardless, muscular Christ raises his hand in final judgment, his gesture both commanding and restrained.

The painting caused immediate controversy. The nude figures scandalized Church officials (leading to later “cover-ups” by another artist), while the chaotic composition broke from traditional Last Judgment imagery. Personal touches abound: St. Bartholomew holds his flayed skin, the face of which is a self-portrait of the aging Michelangelo. The artist also included figures from Dante’s Inferno and portraits of critics being dragged to hell—his subtle revenge on detractors.

Travel Tip: Position yourself near the chapel’s center to take in the full impact. The lower right corner (damned souls) contains some of Michelangelo’s most expressive figures.

10. Raphael’s Transfiguration (1520) – Vatican Museums

Raphael’s final masterpiece combines two biblical events—Christ’s transfiguration atop Mount Tabor (upper section) and the failed exorcism of a possessed boy (lower section). The painting’s dual composition creates dramatic tension between divine glory and human suffering. Christ floats in radiant light between Moses and Elijah, while below, the apostles struggle to heal the boy as his desperate family looks on.

The work showcases Raphael’s mature style—the dynamic composition, emotional depth, and masterful handling of light. The boy’s twisted pose and pale skin contrast sharply with Christ’s serene luminosity. Interestingly, the painting was unfinished at Raphael’s death (his pupil Giulio Romano completed some figures), making it a poignant testament to the artist’s legacy.

Travel Tip: This painting now has its own room in the Vatican Pinacoteca. Visit after seeing the Sistine Chapel to appreciate how Raphael’s style differed from Michelangelo’s.

11. Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes (1599) – Rome

In Palazzo Barberini, Caravaggio’s brutal depiction of the biblical heroine Judith decapitating the Assyrian general Holofernes remains shockingly visceral. The painting captures the precise moment when Judith’s blade slices through Holofernes’ neck, his mouth frozen in a scream, blood spurting onto the sheets. Judith’s expression mixes determination with revulsion, while her elderly accomplice Abra waits eagerly with a sack.

Caravaggio’s signature chiaroscuro heightens the drama—the figures emerge from darkness as if spotlighted on a stage. The composition’s diagonal lines (Judith’s arms, Holofernes’ twisting body) create dynamic tension. Some scholars believe Caravaggio used a mirror to paint himself as Holofernes’ screaming face, adding psychological complexity to the scene.

Travel Tip: Palazzo Barberini is less crowded than Rome’s bigger museums. Visit in the afternoon when the light best illuminates Caravaggio’s dramatic contrasts.

12. Veronese’s The Wedding at Cana (1563) – Venice

At the Accademia Gallery, Veronese’s massive canvas (22 feet wide!) transforms the biblical wedding feast into a dazzling Venetian party. Over 130 figures populate the scene—from the bride and groom at center to the musicians in the foreground (including portraits of Veronese, Titian, and Bassano playing instruments). The composition leads the eye to Christ performing his first miracle—turning water into wine—almost as an afterthought in the lower right.

Veronese’s genius lies in the details: the rich fabrics, the architectural setting inspired by Palladio, the play of light on glassware. When the painting was moved from its original monastery to Paris by Napoleon, workers had to remove a wall to extract it. A full-scale copy now hangs in the original location at San Giorgio Maggiore.

Travel Tip: Use the mirrors provided to appreciate details in the upper sections without straining your neck. The Accademia’s lighting is best in mid-morning.

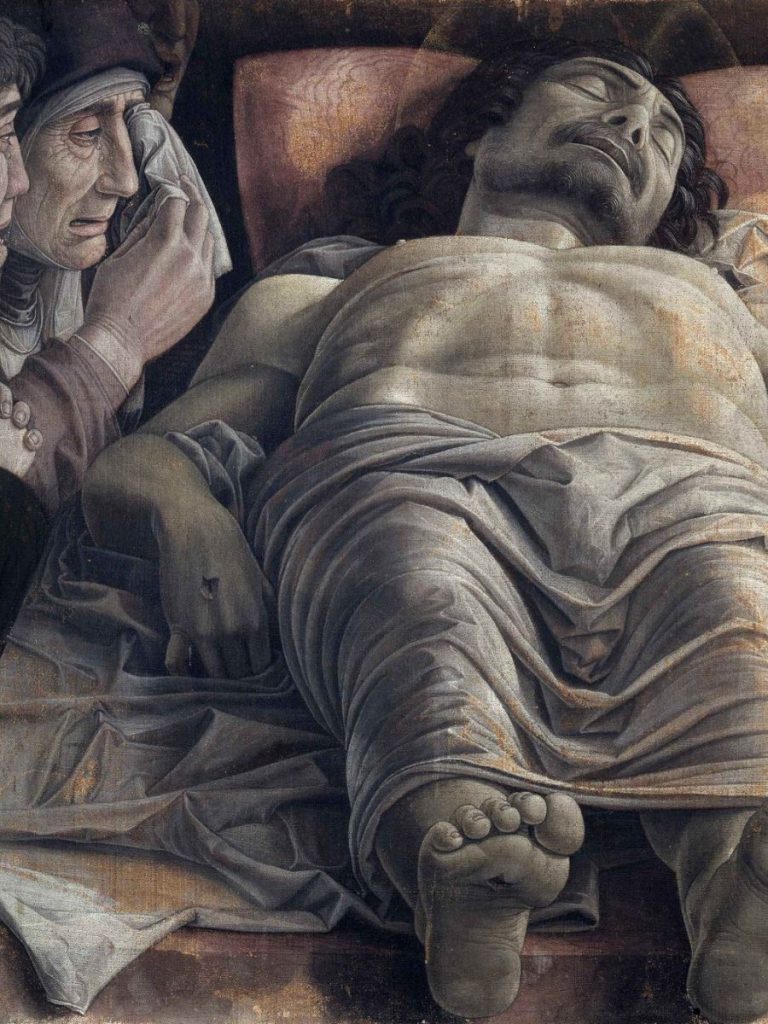

13. Mantegna’s The Dead Christ (1480) – Milan

In the Pinacoteca di Brera, Mantegna’s radical foreshortened Christ forces viewers to confront mortality head-on. The stark composition—with Christ’s lifeless body filling the frame and his pierced feet dominating the foreground—creates an intimate, almost claustrophobic effect. The anatomical precision (notice the rigor mortis in the hands) reflects Mantegna’s archaeological interests.

The painting’s emotional power comes from its simplicity. The grieving Virgin and St. John are reduced to small figures in the background, while the cold stone slab emphasizes Christ’s isolation in death. The subtle wounds and grayish skin tone make the scene painfully real, yet the careful perspective maintains a sense of dignity.

Travel Tip: Brera’s collection is wonderfully varied. Pair this with Raphael’s Marriage of the Virgin in the same room to compare different Renaissance approaches to sacred subjects.

14. Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes (1620) – Florence

In the Uffizi’s dedicated Caravaggio room, Gentileschi’s violent masterpiece channels personal trauma into art. The painting shows the moment Judith (a self-portrait?) and her maidservant Abra behead the drunken general Holofernes. The blood sprays realistically as Judith saws through muscle with grim determination—a far cry from earlier, more decorous versions of the scene.

Gentileschi, who was raped by her painting teacher and endured a humiliating trial, brings unique intensity to the subject. The strong diagonal composition and dramatic lighting show Caravaggio’s influence, but the emotional rawness is all Gentileschi’s. Some see it as feminist revenge fantasy; others as a testament to resilience. Either way, it’s unforgettable.

Travel Tip: This painting hangs near Caravaggio’s Medusa—compare their treatments of violence. The Uffizi’s new lighting enhances the blood’s vivid red.

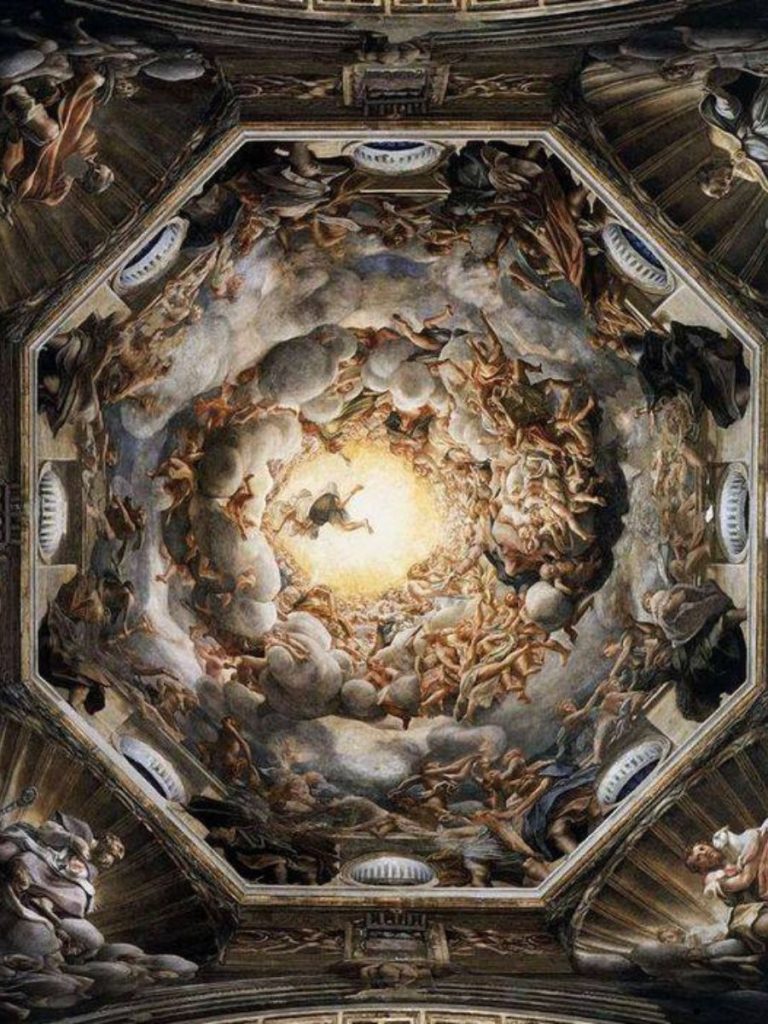

15. Correggio’s The Assumption of the Virgin (1530) – Parma

Parma Cathedral’s dome fresco creates the illusion of heaven opening above worshippers. The Virgin ascends through concentric rings of joyful angels toward the waiting Christ, while astonished apostles gape below. Correggio’s mastery of perspective makes the figures appear to float in real space—a technique that would inspire later Baroque ceiling painters.

The composition’s swirling energy is breathtaking. Clouds dissolve into golden light as figures tumble in ecstatic motion. The apostles’ varied reactions—from awe to skepticism—add human scale to the divine spectacle. When first unveiled, some criticized its unconventional style, but it soon became a model for illusionistic ceiling painting across Europe.

Travel Tip: Bring binoculars to appreciate details in the upper sections. Visit around noon when sunlight enhances the golden tones.

Making the Most of Italy’s Artistic Treasures

After decades of guiding travelers, I’ve learned that great art appreciation requires three things:

- Context – Understanding a work’s history and symbolism transforms viewing from passive to profound.

- Timing – Early mornings or late afternoons offer quieter moments with masterpieces.

- Pacing – Limit yourself to 3-4 major works per day to avoid “museum fatigue.”

Remember, you’re not just seeing paintings—you’re engaging in a centuries-old conversation about beauty, faith, and human experience. As the Italians say, “A museo lento”—in museums, go slow. May these fifteen masterpieces be just the beginning of your own Italian artistic journey.