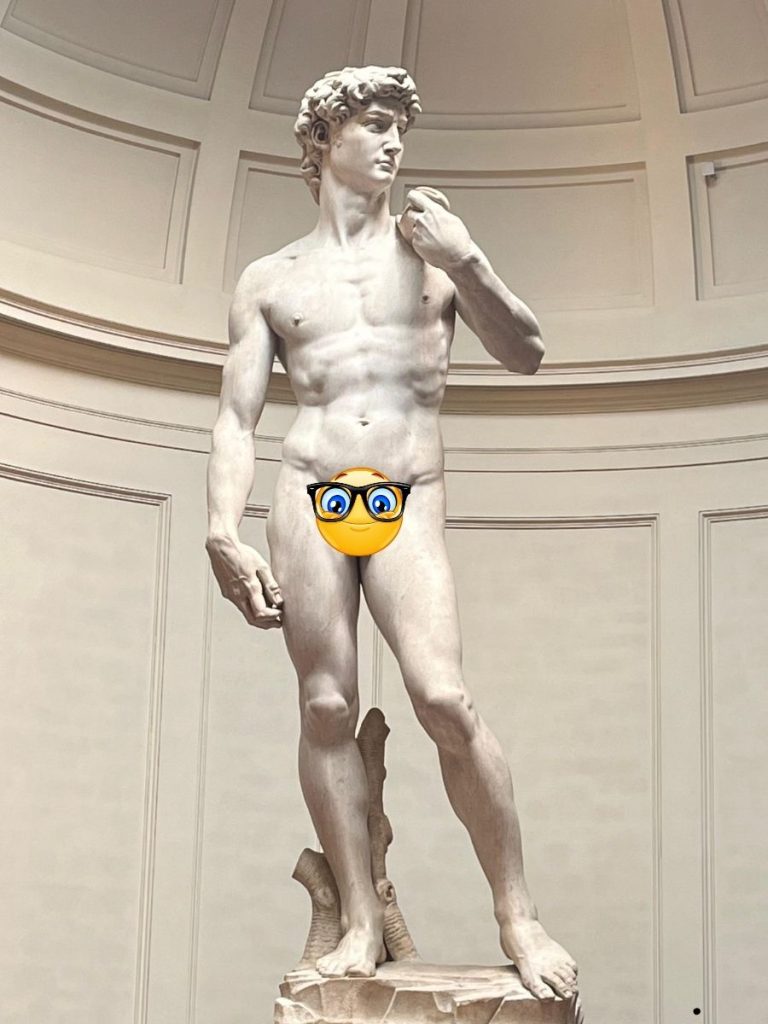

After waiting outside the Accademia Gallery for about 30 minutes—despite having booked a skip-the-line ticket weeks in advance—I was finally ushered inside to see the masterpiece I’d always dreamed of: Michelangelo’s David!

I’d already seen the replicas in Piazza della Signoria and Piazzale Michelangelo, but I wanted to experience the real thing—and it didn’t disappoint. What shocked me most was David’s sheer size and the incredible attention to detail. Since we’d just come from Rome, I turned to my wife and asked which she found more impressive: David or The Pietà (which we’d spent nearly 30 minutes admiring at the Vatican). It’s astounding to think Michelangelo sculpted both these masterpieces and then went on to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling (a must-see, by the way).

We took countless photos and videos of David before exploring the rest of the gallery. In this post, I’ll share my 11 favorite sculptures in Italy—let me know in the comments if you agree! What do you think is the best sculpture in Italy… or even the world?

So, let’s ditch the vague travel fluff. We’re going deep. You’ll learn why these statues matter, where to find them, and the wild histories behind them. By the end, you’ll be booking a flight just to stand in their shadows. Ready? Let’s begin.

1. David by Michelangelo – Florence, Galleria dell’Accademi

There’s confident, and then there’s David. Michelangelo’s 17-foot-tall marble masterpiece isn’t just a statue—it’s a defiant triumph of artistry, a bold challenge to the ordinary. Carved from a discarded block of marble that two other sculptors had given up on, David embodies the Renaissance ideal: perfect proportions, intense focus, and the quiet swagger of a man who knows he’s about to win. Unlike earlier depictions of David post-victory, Michelangelo shows him before the fight with Goliath, muscles taut, veins pulsing, eyes locked on his enemy. It’s raw, human tension frozen in stone.

Originally placed in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria (now home to a replica), David was a political symbol for the Florentine Republic—a small city-state defiant against giants like Rome and Milan. Today, he presides over the Accademia’s tribune like a rockstar, bathed in natural light that makes the marble glow. Fun fact: Michelangelo was only 26 when he started it. Let that sink in next time you’re proud of assembling IKEA furniture.

Visiting Tips: The Accademia is small but packed. Book a skip-the-line ticket for sunrise slots to avoid crowds. Don’t rush past the “Prisoners” sculptures nearby—they’re unfinished Michelangelo works that show his “freeing the figure from stone” technique. And yes, everyone does stare at David’s hands. (They’re deliberately oversized for dramatic effect.)

2. The Pietà by Michelangelo – Vatican City, St. Peter’s Basilica

If David is strength, the Pietà is heartbreak. Michelangelo’s first major commission, completed when he was just 24, depicts the Virgin Mary cradling Christ’s lifeless body with devastating tenderness. The folds of her robes, the slump of his limbs, the sorrow in her downcast eyes—it’s grief carved so softly, you half-expect the marble to sigh. What’s insane is that Michelangelo made Mary look younger than Jesus, a theological choice: her purity, not age, defines her.

The Pietà is also the only sculpture Michelangelo ever signed. Legend says he overheard visitors crediting it to another artist, so he snuck in at night and carved “MICHAEL ANGELUS BONAROTUS FLORENTIN FACIEBAT” (“Michelangelo Buonarroti, Florentine, made this”) across Mary’s sash. Later, he regretted the ego move and never signed another piece. Today, the statue sits behind bulletproof glass since a deranged geologist attacked it in 1972, screaming, “I am Jesus Christ!”

Visiting Tips: St. Peter’s Basilica is free, but lines snake for hours. Go early morning or late afternoon. The Pietà is immediately to the right upon entering—don’t miss the faint crack in Mary’s left elbow (from the 1972 hammer strike). For the best view, bring binoculars to spot Michelangelo’s signature.

3. The Rape of Proserpina by Bernini – Rome, Galleria Borghese

Baroque drama doesn’t get more intense than this. Gian Lorenzo Bernini was 23 when he carved Pluto abducting Proserpina, and the result is so visceral, you’ll wince. Look at Pluto’s fingers digging into Proserpina’s thigh—the marble looks soft. Her tears, the wind in her hair, the Cerberus snarling at their feet—it’s a mythological snapshot with the energy of a blockbuster movie. Bernini didn’t just sculpt figures; he sculpted motion.

The Borghese family, who commissioned it, were notorious art hoarders (and occasional criminals). Cardinal Scipione Borghese demanded this piece as a power flex, and Bernini delivered. The twist? Proserpina’s eventual return to Earth (thanks to a deal with Pluto) symbolized the changing seasons—a fancy way to say even kidnappings can have happy endings.

Visiting Tips: The Galleria Borghese requires reservations (only 360 visitors allowed every 2 hours). Book weeks ahead. The statue sits in Room IV—spend time circling it to catch details like Proserpina’s pushed-out hip, a trick to show her struggling. Pair your visit with Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne in the next room—another “how is this stone?!” masterpiece.

4. The Bronze Statue of Marcus Aurelius – Rome, Capitoline Museums

Let’s talk about survival. This gilded bronze equestrian statue of philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius is one of the only ancient Roman bronzes to escape being melted down for weapons or coins. Why? Because everyone thought it was Constantine the Great, Rome’s first Christian emperor. The mistake saved it—and thank God, because it’s a masterpiece. The emperor’s outstretched hand once held reins (now lost), but his calm, slightly weary expression steals the show. This isn’t a conquering hero; it’s a leader burdened by power.

The statue’s current home, the Capitoline Museums, was designed by Michelangelo himself. He placed it atop a pedestal in the center of Piazza del Campidoglio, where it stood for centuries before being moved indoors to protect it from pollution. The one you see outside today? A perfect replica. The original now sits in a specially designed hall, where you can walk around it and marvel at the intricate details—like the veins in the horse’s legs and the emperor’s finely detailed sandals.

Visiting Tips: The Capitoline Museums are often overlooked in favor of the Vatican, but they’re a treasure trove of ancient art. Buy a combined ticket with the Roman Forum for maximum history immersion. The Marcus Aurelius room is dimly lit to preserve the bronze—let your eyes adjust to appreciate the statue’s golden glow. And don’t miss the Spinario (the “thorn puller”) nearby—a charming Hellenistic bronze of a boy removing a splinter from his foot.

5. Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne – Rome, Galleria Borghese

If you’ve ever been friend-zoned, you’ll feel this statue. Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne is the ultimate unrequited love story, carved in marble with such insane detail, you’ll forget it’s stone. The moment captured is pure mythological drama: the god Apollo, struck by Cupid’s arrow, chases the nymph Daphne, who’s mid-transformation into a laurel tree to escape him. Her fingers sprout leaves, her toes root into the earth, and her face is a mix of terror and relief—like she’s thinking, “Worth it.”

Bernini was 23 years old when he made this. Let that sink in. The way he carved Daphne’s bark-covered skin, Apollo’s flowing drapery, and the windblown hair of both figures is pure sorcery. The statue was commissioned by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, a patron with a flair for drama (and a shady reputation). It’s meant to be walked around—from Apollo’s desperate lunge to Daphne’s backward glance, every angle tells part of the story.

Visiting Tips: The Apollo and Daphne shares the Galleria Borghese with Bernini’s Rape of Proserpina (another showstopper). Book tickets months ahead—time slots sell out fast. The statue sits in Room III, and the best view is from Daphne’s left side, where you can see her fingers morphing into branches. Fun fact: A small, hidden Borghese family crest is carved into the tree trunk—because even art this sublime needed a branding opportunity.

6. The Four Tetrarchs – Venice, St. Mark’s Basilica

Here’s a statue with a backstory wilder than a Game of Thrones plot. These four figures, carved from rare purple porphyry marble, represent the Tetrarchy—a Roman power-sharing system where four emperors ruled together (spoiler: it didn’t last). What’s fascinating is how stiff and identical they look—no individuality, just unity in power. The embrace between two of them isn’t a hug; it’s a political statement.

The real kicker? These guys were looted from Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade in 1204 and stuck onto the corner of St. Mark’s Basilica like a trophy. Venice wasn’t subtle about its plunder. One of the Tetrarchs is missing a foot—it was found in Istanbul in the 1960s and is now in a museum there. Talk about a long-distance breakup.

Visiting Tips: The Tetrarchs are on the southwest corner of St. Mark’s Basilica, easy to miss if you’re not looking. They’re small (about 4 feet tall) but pack a historical punch. Visit early morning when the square is quiet—the way the light hits the porphyry makes the stone look almost alive.

7. Bernini’s Fountain of the Four Rivers – Rome, Piazza Navona

If you’ve ever wondered what it looks like when a Baroque genius throws a marble block party, this is it. Bernini’s Fountain of the Four Rivers isn’t just a fountain—it’s a geopolitical flex, an engineering marvel, and Rome’s ultimate gossip magnet. Towering in the center of Piazza Navona, it represents four major rivers (Nile, Ganges, Danube, and Río de la Plata) as muscled river gods, each reacting to the church of Sant’Agnese behind them. The Nile covers his face (allegedly because its source was unknown then), the Ganges holds an oar (for navigability), the Danube touches the papal coat of arms (symbolizing Europe’s Catholic heart), and the Río de la Plata sits on coins (for New World wealth). Oh, and there’s a *25-ton Egyptian obelisk* balanced on top like a dare.

The drama behind this fountain is juicier than a Renaissance soap opera. Pope Innocent X commissioned it in 1651 to outshine his family’s rival, the Pamphilj, whose palace faced the square. Rumor says Bernini won the job by sneaking a silver model into the pope’s dining room. His secret? The obelisk isn’t anchored—it’s hollow, resting on carefully calculated arches so the water’s roar echoes inside. The locals swore it would collapse for centuries. Spoiler: It didn’t.

Visiting Tips: Piazza Navona is always open and free, but go at dawn to avoid crowds. Stand near the Río de la Plata figure—the way Bernini carved his terrified expression (allegedly reacting to Sant’Agnese’s unstable facade) is a masterclass in stone side-eye. Want a true Roman experience? Grab a tartufo ice cream at Tre Scalini and debate whether the lion and palm tree were digs at rival architect Borromini.

8. Neptune Fountain – Bologna, Piazza del Nettuno

Giambologna’s Neptune Fountain is Bologna’s mascot—a brawny, bearded god surrounded by sirens, cherubs, and water-spouting sea creatures. The locals call it “Il Gigante” (The Giant), and it’s easy to see why. Neptune’s trident allegedly inspired the Maserati logo, and students have a superstition: walking clockwise around the fountain before exams brings bad luck. (They’re not taking chances.)

The fountain was built in the 1560s as a flex by Pope Pius IV, who wanted to show off Bologna’s wealth. The water jets were originally a high-tech marvel, and Neptune’s muscular pose (leaning forward like he’s about to dive) was revolutionary for its time.

Visiting Tips: The fountain is free and always accessible, but it’s best at night when lit up. Nearby, grab a gelato at Gianni and people-watch. Fun fact: The statue’s private parts were covered with a bronze leaf in the 1600s after complaints from the Church.

9. The Capitoline Wolf – Rome, Capitoline Museums

This bronze she-wolf, suckling Romulus and Remus, is the ultimate symbol of Rome. The twist? The wolf might be Etruscan (5th century BCE), while the twins were added in the Renaissance. The statue was struck by lightning in 65 BCE (a bad omen), stolen by the Vandals, recovered by the Pope, and later gifted to the city. Today, it’s a cultural icon—replicas stand everywhere from New York to Bucharest.

Visiting Tips: The original is in the Capitoline Museums’ Palazzo dei Conservatori. Look closely—the wolf’s tense muscles and alert ears make her seem alive.

10. Perseus with the Head of Medusa – Florence, Loggia dei Lanzi

Cellini’s Perseus is the Renaissance equivalent of a mic drop. The hero stands triumphant, holding Medusa’s severed head, her serpent hair still writhing. The statue was a revenge piece—Cosimo I de’ Medici commissioned it to symbolize his crushing of political rivals. The bronze casting was so difficult, Cellini nearly died from fumes, but the result is flawless.

Visiting Tips: The Loggia dei Lanzi is open-air and free—visit at dusk for dramatic shadows.

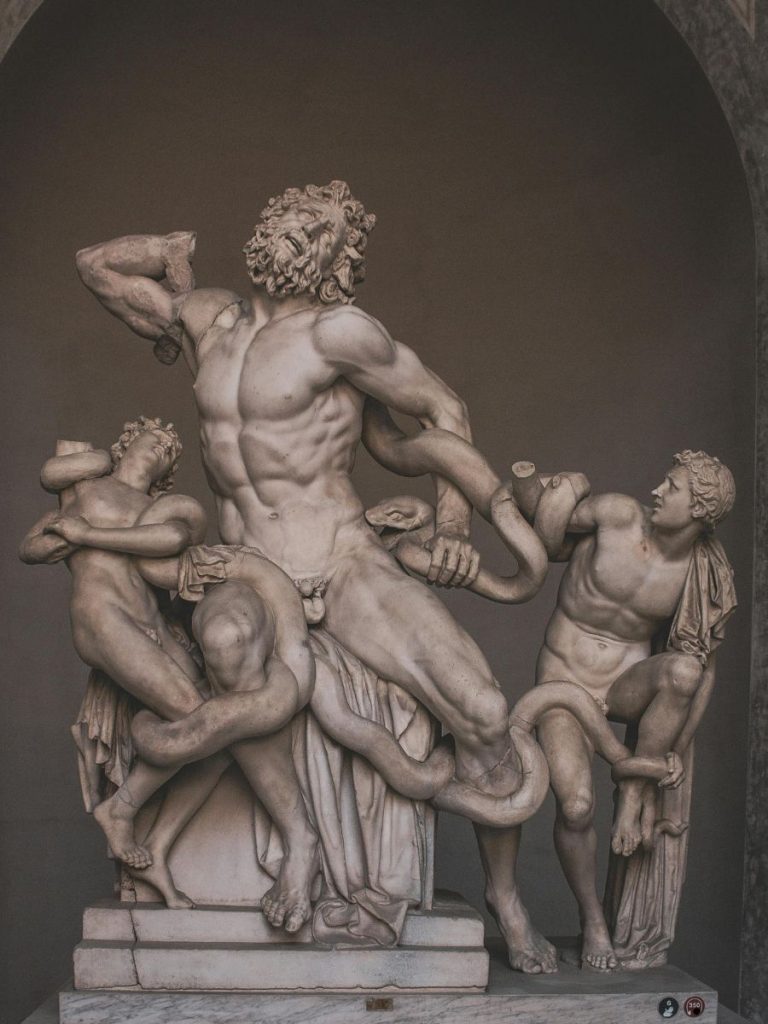

11. Laocoön and His Sons – Vatican City, Vatican Museums

Few sculptures in history have screamed louder – both literally and metaphorically – than the Laocoön and His Sons. This 1st-century BC Hellenistic masterpiece captures the tragic moment when the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons are attacked by sea serpents sent by the gods. The contorted bodies, bulging muscles, and faces twisted in agony make this one of the most emotionally intense sculptures you’ll ever see.

Discovered in 1506 near Nero’s Golden House, the excavation was so significant that Pope Julius II sent Michelangelo to verify its authenticity. When Michelangelo saw it, he reportedly said, “This is the Laocoön mentioned by Pliny” – recognizing it from ancient descriptions. The sculpture’s rediscovery became a watershed moment for Renaissance art, influencing Michelangelo’s own muscular style in works like The Last Judgment.

Visiting Tips: The Laocoön holds pride of place in the Pio-Clementine Museum at the Vatican. Come prepared – it’s located deep in the museum complex after rooms of other antiquities. Early morning visits are best to avoid crowds. Look closely at the restoration work – the priest’s right arm was originally thought to be reaching backward until the original bent arm was found in 1905. The dramatic composition looks best from the left side at about a 45-degree angle.

Little-Known Fact: This sculpture was so revered that when Napoleon stole it in 1799, the Treaty of Tolentino specifically mentioned its removal. It was returned after his defeat and now sits in an alcove designed by Bramante – making this one of the few artworks whose display space was architecturally customized for it.

The Laocoön’s influence can’t be overstated. It’s been called “the prototypical icon of human agony” in Western art, inspiring works from Titian’s paintings to the famous “Alien” movie creatures. Its discovery literally changed how artists depicted the human form in motion and emotion. When you stand before it today, you’re seeing the sculpture that redefined Renaissance art – and still takes our breath away 2,000 years later.

Final Thoughts

These statues aren’t just art—they’re time machines. Stand before them, and you’re face-to-face with emperors, gods, and geniuses who shaped history. So tell me—which one calls to you?

Now go. Italy’s marble legends are waiting.